Office design trends tend to swing like a pendulum. A few generations ago, many white-collar workers toiled in private offices or high-walled cubicles, only to see those walls torn down in favour of airy open-plan spaces in the 2000s. Tech companies championed open offices as egalitarian and collaborative, packing employees into “cool” loft-like spaces without partitions. By 2020, roughly two-thirds of U.S. knowledge workers sat in open layouts. But then came the hybrid-work era and a reassessment of what the office is for.

Many find themselves nostalgic for the cubicle – craving the privacy and focus it once afforded. This raises a timely question: are cubicles a relic of the past, or could they be a key tool for today’s workplace? Put differently: can modern, semi-enclosed workstations deliver the focus people want without dragging us back to grey mazes and “Do Not Disturb” signs?

A Brief History of the Cubicle

The cubicle wasn’t created to be soulless or dull; it was born of utopian intentions. In the early 20th century, modernist architects like Frank Lloyd Wright railed against “confines of boxes,” promoting open-plan offices as liberating alternatives to rigid private rooms. Companies adopted open layouts, largely to accommodate more clerks in “white-collar assembly lines” of desks.

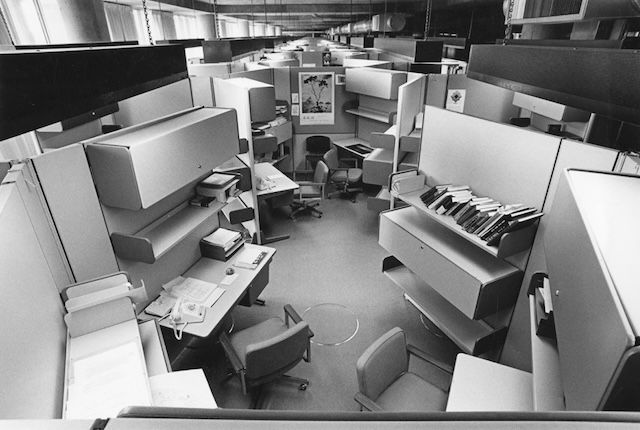

By the 1960s, this efficiency drive had drained offices of privacy and personality. Enter the Action Office: a 1964 innovation by Herman Miller (and designer Robert Propst) that introduced modular workstations with partitions, varying desk heights, and larger surfaces. These early cubicles aimed to humanize the office, breaking up endless desk rows into flexible clusters (the German Bürolandschaft, or office landscape) that offered workers a bit of enclosure and personal spaces.

However, the cubicle’s idealistic origins were soon undermined. By 1968, Herman Miller was selling modular cubicle components, which some cost-conscious firms abused – cherry-picking the space-saving aspects (tiny, uniform panels) and discarding the humanising touches. As more companies shifted all ranks of employees (not just clerks) into cubicles, Propst himself regretted the outcome, decrying the “monolithic insanity” he had inadvertently spawned.

In the 1980s and ’90s, the cubicle became ubiquitous and unloved. Pop culture of the late ’90s (from Office Space to Dilbert) immortalised the cube farm as a symbol of corporate drudgery.

Why Did Cubicles Go Away?

The answer lies in a mix of management ideology, economics, and aesthetics. Around the turn of the millennium, a new generation of leaders inspired by Silicon Valley startups viewed cubicles as antithetical to innovation.

The open-plan office promised to break down silos, foster spontaneous collaboration, and equalise the workplace by putting the CEO and intern at identical desks. Google’s widely emulated 2005 headquarters design epitomised this shift. Workers were rebranded as “teams,” managers became “leaders,” and collaborative buzz was seen as the key to creativity. Enclosed workstations felt outdated in this new narrative of transparency and interaction.

Cost was another driving force. In high-rent markets like New York and London, giving everyone a roomy cubicle (let alone a private office) was simply too expensive. Densifying into bench-style desks or tables without partitions allowed companies to lease less space per employee – a tempting proposition for the bottom line.

Indeed, the late 1990s and 2000s saw cubicles rapidly disappear, replaced by seas of shared desks. As one furniture design executive noted, “putting everyone in a cubicle or office was too much, so the open-floor plan became very popular” during that era.

Do Cubicle Offices Still Exist?

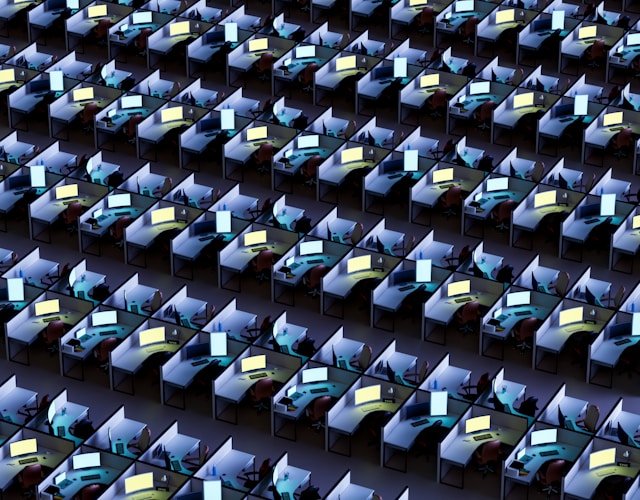

Even at the height of the open-office craze, cubicles never disappeared entirely. Some organisations retained some partitioned work areas, especially in industries where noise control or confidentiality is paramount. Government agencies, insurance companies, call centres and other operations handling sensitive data often stuck with low-walled cubicles well into the 2010s. In fact, a sizable global market for office partitions persisted.

Back in 2023, global demand for cubicles and panels was valued at around $6.3 billion and projected to grow to $8+ billion in the next five years. This suggests that tens of millions of people worldwide still sit in semi-enclosed workspaces, even if tech giants and trendsetting startups grab more headlines with their lounge-like open floors.

To be fair, today’s cubicle installations don’t always resemble the classic 1980s cube farm. Many offices have employed a hybrid approach – e.g. clusters of low partitions within a mostly open layout, or high-walled focus booths sprinkled among open team tables. In some modern spaces, you’ll find “pods” or “neighbourhoods” that include a mix of open desks, standing-height counter space, and a few enclosed cubicle-like nooks for quiet work.

The terminology may have shifted (a few companies proudly announce “we installed cubicles!”), but the core concept of partially partitioned personal work areas is still very much alive. And as we’ll explore next, these semi-cubicles might be poised for a modest revival in the near future.

Are Cubicles Coming Back?

There are growing signs that the cubicle – or at least the idea of more enclosed individual space – is making a comeback in response to post-pandemic workplace needs. In late 2023, The New York Times reported a renewed interest in cubicles as companies seek to address noise and privacy complaints in open offices. With widespread hybrid work, employees now often come into the office specifically to do work they can’t easily do at home (e.g. access specialised equipment, meet with colleagues) – but they also expect the office to support concentration. Janet Pogue McLaurin, a workplace research leader at Gensler, noted that when workers returned after months at home, “quiet spaces became more important” because many offices had seen “a drop in effectiveness due to noise interruptions, disruptions and a general lack of privacy”.

In other words, the mass experiment of remote work taught employees what uninterrupted focus feels like, and they’re now less tolerant of the open-plan racket.

Orders for partitions and modular walls are rising (on track for ~30% growth this decade), and office furniture makers are rolling out new product lines that reinvent the cubicle for modern needs. Today’s designs are not your father’s gray fabric boxes: modern cubicles are more flexible and stylish. Some high-end models include sound masking systems or sliding doors. The goal is to create a “semi-private haven” within a busy office, a place where an employee can take a video call or work on a focused task without being both visually and audibly exposed to the entire floor.

56% of organisations are adding private phone booths and focus rooms for privacy

It’s worth noting that the push for cubicles 2.0 isn’t solely driven by pandemic-related health concerns (though plexiglass shields did briefly pop up everywhere in 2020). Even before COVID, many companies had begun sprinkling phone booths and focus pods into open layouts. The pandemic accelerated this by highlighting airborne risks and the value of physical separation, but arguably the bigger driver now is productivity and preference.

In a mid-2025 occupancy planning survey, 56% of companies said they were adding private phone booths or focus rooms to meet employee needs for privacy, even as they also expand collaboration areas. After more than a decade of “open everything,” design strategies are shifting to reintroduce more enclosure for focused work while still enabling teamwork.

Do People Like Working in Cubicles?

Do people like cubicles? It depends on the proportion you have. Go all-in on cubicles and you risk a flat, isolating vibe; go all-in on open plan and you fuel noise, distractions, and headset culture. Most teams are unhappy at either extreme.

When the balance tilts too far open, focus drops fast: 63% of employees say they lack a quiet place to work, 75% admit they leave the office just to concentrate, and only 1% feel able to block out distractions. An open office layout helps some tasks, but not deep work.

You can swing the other way with wall-to-wall cubes and it can be just as problematic. Only 12% of U.S. office workers say they prefer a traditional cubicle layout (Gensler). High, uniform panels dull energy, reduce visibility, and make chance interactions less likely.

The sweet spot is a mix, not a monoculture. A clear majority (65%) prefer open areas for group work plus genuinely quiet, semi-enclosed spots for focus (Gensler). Where noise is controlled, employees report higher ability to work productively; private offices top acoustic satisfaction at 56%, while bench seating sits at 28%. In practice, that means just-enough walls where and when people need them, that’s privacy on demand without killing the vibe.

Cubicles as a Tool, Not a Doctrine

Reconsidering cubicles doesn’t mean swinging the pendulum all the way back to the era of identical boxes and maze-like layouts. It means acknowledging that the “one big room” open-office experiment has its shortcomings, and that a balanced workplace includes some places to tune out and focus. The cubicle, in its updated forms, is simply one tool among many to craft a high-performing office. Just as we have embraced agile, activity-based work and remote connectivity, we can also embrace a bit more physical delineation in the office when it helps people do their best work.

If there is one takeaway from this article, it is that no single office layout wins universally. A mix of open and enclosed, communal and private, assigned and flexible – tailored to an organisation’s unique needs – tends to yield the best outcomes. So rather than asking “open plan or cubicles, which is better?”, the forward-thinking question is “what is the right combination of spaces for our people and our work patterns?”

Cubicles still have a role, but not as a doctrine forced on everyone, but as a flexible tool deployed with purpose.